- Canelo

Canelo finds the best commercial storytelling and brings it to the widest possible audience. Visit Canelo Website

- |Canterbury Classics

Canterbury Classics publishes classic works of literature in fresh, modern formats. Visit Canterbury Classics Website

- |Dreamtivity

Dreamtivity publishes innovative arts & crafts products for all ages. Visit Dreamtivity Website

- |Portable Press

Portable Press publishes fun trivia and reference books for the whole family. Visit Portable Press Website

- |Silver Dolphin

- |Studio Fun

Studio Fun International produces engaging and educational books and books-plus products for kids of all ages. Visit Studio Fun Website

- |Thunder Bay

Thunder Bay Press brings information to life with highly visual reference books and interactive activity books and kits. Visit Thunder Bay Website

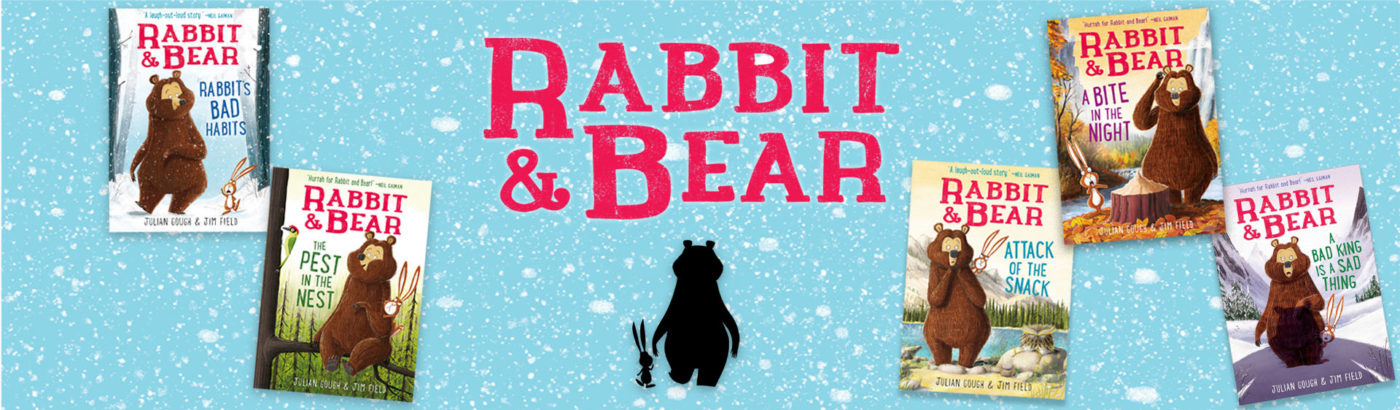

An Interview with Author Julian Gough

Photo credit: Juliana Socher

Tell us a bit about yourself and how you became an author.

Well, my parents are Irish, but I was born in London. My dad was a fireman at Heathrow Airport, and we lived right at the end of the runway. I loved it. The Concorde would fly over our house and shake my toy cars off the windowsill. I got so used to planes flying over the house every three minutes that I remember I woke up one night with a jolt, and ran to my parents’ room to ask what had happened. What had happened was, there had been a strike; planes had stopped flying over us and I was woken up by the silence. So I was a happy big-city kid. I loved being read to, but I didn’t bother learning how to read.

But when I was seven we moved back to Ireland, and lived in the countryside, and had no TV, and I was so bored I learned how to read in about two weeks. And as soon as I learned how to read, I wanted to write. I was just fascinated by the magical ability of those black marks on a page to conjure up a totally convincing world inside your head. I wanted to know how it was done; I wanted to do it. And so I started writing at age seven, and wrote terribly, on and off, for a couple of decades, until eventually I got better at it.

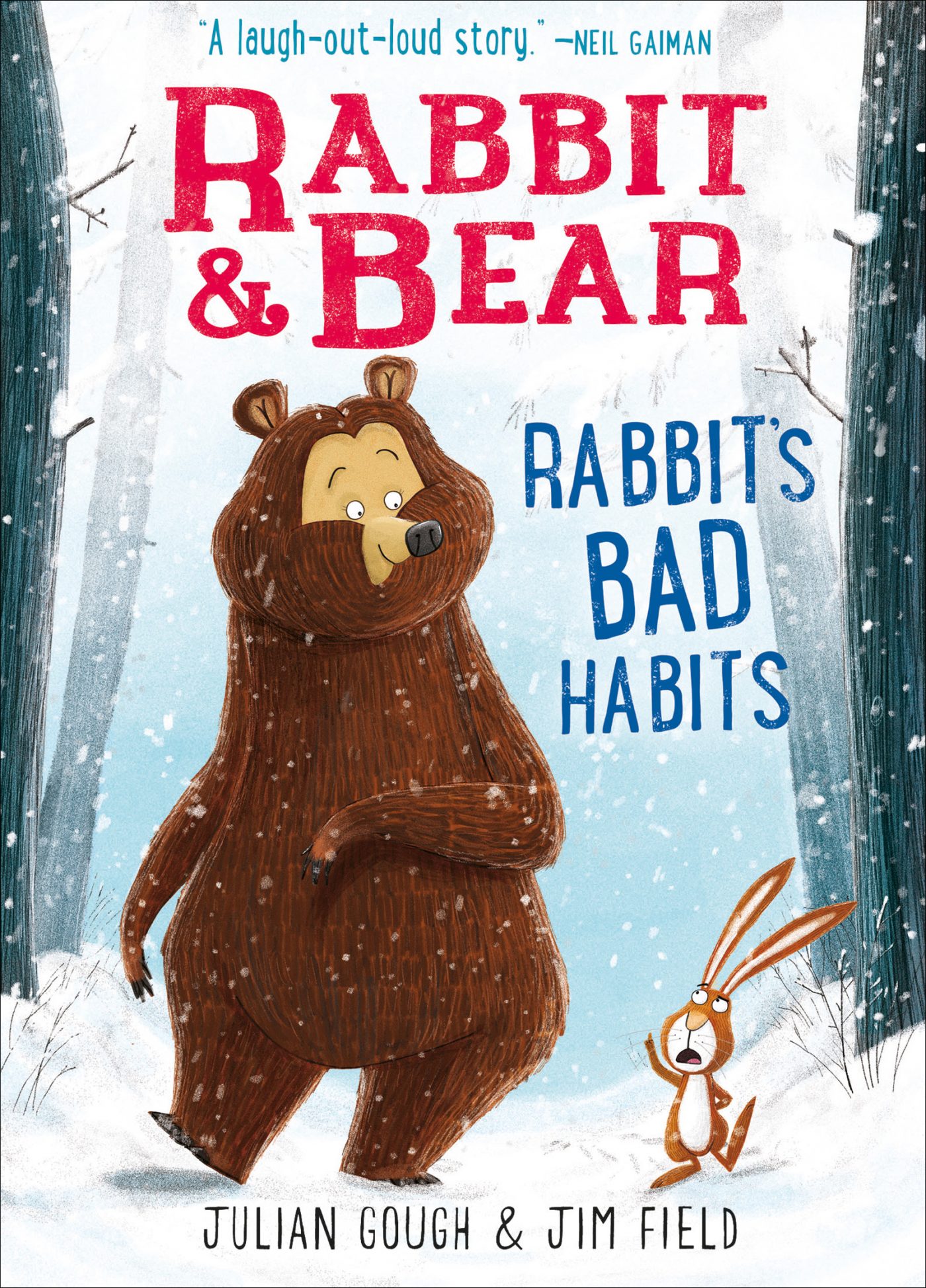

Rabbit & Bear: Rabbit’s Bad Habits was your first children’s book. What inspired you to write a children’s book?

My daughter Sophie. I read to her every night for years, I loved that ritual. But one night I read her a book that was so boring, I started to criticize it aloud as I read it. I guess I had been editing one of my own novels earlier that day, so I was in editing mode, and this book just infuriated me because nothing interesting happened. And my daughter, who was five or six at the time, joined in, and we both started making suggestions to improve it. The book I’d been reading (I think it was a well-meaning present from a relative who didn’t have children and didn’t know anything about children’s books) was about a rabbit and a bear who were nice to each other, and cooperated, and there was absolutely nowhere for the story to go because there was no conflict, no real problem; it just wasn’t a story. So, we made up a new story where they didn’t like each other at all. The Rabbit was grumpy and mean to the Bear, and there was a ton of conflict. It was fun. In the book we had been reading, a third animal turned up at some point, but he was just another boring friendly animal and did nothing, in story terms. So Sophie said, “What if the new animal was a wolf, and then he could chase the rabbit?” “Brilliant!” I said, so we did that. And after she had fallen asleep I left her room and closed the door and thought: our story is so much better than the published book. I should really do something with it. So I wrote it down, and the next night I read it to Sophie as her bedtime story. She loved it, and afterwards we chatted about how we could make it even better…and so, over the next few months we kept improving it. And it eventually turned into the first Rabbit & Bear book, Rabbit’s Bad Habits. And I loved the characters we had created; I thought I could do a lot with them, so I wrote more.

Do you have a favorite place to write?

We have a south-facing balcony, six floors up, in a brutalist 1950s concrete tower block, with an insanely great view. The light can be too bright for the screen of my old laptop, but if I’m working on paper, I love sitting out there. You can see the Tiergarten (the biggest park in Berlin), the Fernsehturm (the big tower that looks like an olive on a cocktail stick), the Reichstag (the German parliament, a wonderful old stone building with a new glass dome), the Siegesaule (the victory column with a golden angel on top; it’s the place shown at the start of the film Wings of Desire, where Bruno Ganz is a guardian angel, sitting on the statue, and looking down over Berlin). And there are rabbits and squirrels and occasionally a fox in our garden below, and trains run by at the end of the garden on four parallel railway lines, like a huge train set. It’s just the craziest view, I love it so much. But it’s a bit distracting.

What was your favorite part of writing the Rabbit & Bear series?

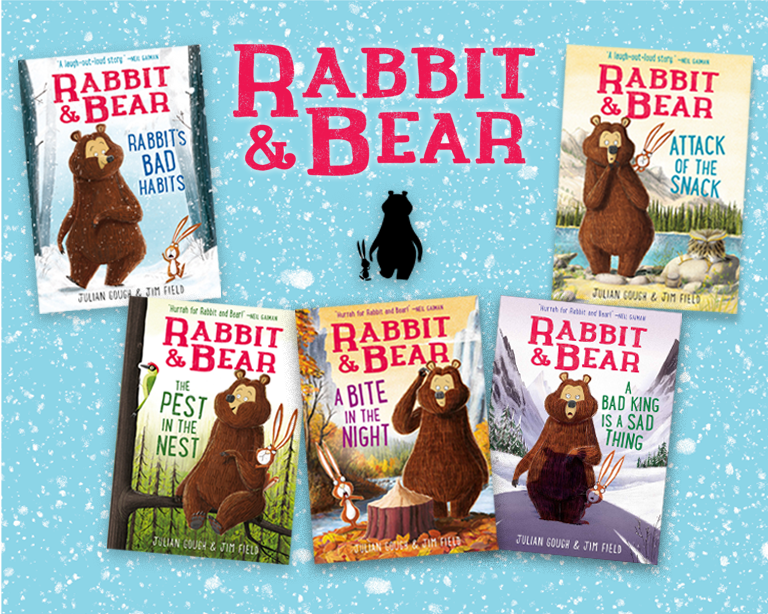

Finishing! Finishing each of the four books! (Editor's note: Stay tuned! The next two books will be available in 2020.) I mean, I do love writing them, but they are really difficult; they take me far longer, per page, than anything else I do. Because the stories have to be so compact, and because you know that children and parents will be reading them again and again and again, every word needs to be the right word. They take me forever. So many drafts. But I’m so proud and happy (and tired) when I’m finally done. When Bear wakes up early from her hibernation, she decides to build a snowman. Her grumpy neighbor, Rabbit, decides to build an even better one. Rabbit & Bear: Rabbit’s Bad Habits is full of laugh-out-loud moments and chronicles the forming of an unlikely friendship.

The illustrations by Jim Field flowed perfectly with each story. Did you have much say in how the characters looked, or did you brainstorm with Jim?

Oh, we work very closely. At the very start, when we were working on the look of the characters, Jim drew a perfect Rabbit; he totally captured him. Bear was a bit trickier to get right, so Sophie and I worked on that with Jim. I remember Sophie and I did a lot of Googling, and sent Jim photos of particular bears that looked like the Bear we saw in our heads. And then he absolutely nailed it, perfect. With each new character, we’ll send him photos to help him. Pictures of, say, a small burrowing owl, rather than a big eagle owl.

Working with Jim is amazing; he’s the perfect artist for the books. He’s technically brilliant, and visually inventive. And he is so good at getting across emotion—in a gesture, in a facial expression. I write the books almost like a script, with a lot of notes that aren’t for publication; they are just for Jim. Sometimes I’ll describe a landscape or a character or a technical thing, like the height of a beaver dam, for Jim; that description won’t need to be in the finished book, because Jim will draw it so well, but he needs it to get the drawing right. Sometimes I’ll suggest a visual joke that isn’t obvious from the story itself. And then he’ll sketch out the whole book, and we’ll go over his rough drawings and tweak things.

At times, it's like working with a brilliant cinematographer. I might say, oh this picture with an angry Rabbit walking towards the reader, looking for a pinecone to throw, is great, very dramatic; could we make it even more dramatic, really push the focus a little, so he’s even closer and almost sticking his face into the camera, almost distorted, like a fish-eye lens, reaching right up to the camera for the pinecone? And he’ll redraw the picture so it’s almost like a Hitchcock shot, so dramatic! Or I might say, could we change Bear’s expression in this shot, so she is less scared and more puzzled? So we have some conversations that are like director and cinematographer, where it’s about the framing and the composition; and some conversations that are more like directing the actors, their expressions, their body language.

And sometimes Jim will suggest something brilliant I would never have thought of. At the end of The Pest in the Nest, with Rabbit in the dark in his burrow, snoring, I had suggested a simple black two-page spread, with a white “ZZZZZzzzzzzZZZZzzzzzz…” But Jim said, “I was in Yosemite a few years ago, at night, and it looked amazing by moonlight. How about I draw the whole valley by moonlight, and have the snoring coming up out of the burrow?” And he did it, and it’s the most beautiful spread in the book, so peaceful.

Jim should win all the awards for these books, because there’s a hundred full pages of illustrations in each one, and every page is worked on and worked on; it’s crazy how much work he puts into them, and how well they turn out.

Gough with Rabbit & Bear Illustrator, Jim Field

What is your favorite project you’ve worked on so far?

Well, with every book, I am trying to find a way to tell a funny story that also, unobtrusively, tells small kids something that I wish I had known myself at their age. Something that will make their life better in some way. And with The Pest in the Nest, I tried to give kids a way to think about their own emotions that I hoped they would find useful, because our emotions are so overwhelming in childhood, we can almost be scared by them. And I’ve heard back from a lot of parents that their children have found it really useful, that they can handle their anger better now, or their sorrow, because of that book. And that makes me feel very emotional as an adult! I nearly cry hearing that. It’s so pleasing, to have been able to help kids in the way I would like to have been helped.

But I have no favorite, or rather they’re all my favorite, because all four have been so enjoyable. On the fourth one, A Bite in the Night, I finally got to go to Paris, where Jim lives, and work shoulder to shoulder with him in his studio, going over every page and discussing every drawing. Before that, we had collaborated mostly by email, sending PDFs back and forth; but to be in the same room, drinking coffee and chatting and working, in Paris, and then to wander over to Montmartre and see original drawings by Van Gogh, Matisse, Degas, Suzanne Valadon, Toulouse-Lautrec…it was great!

What is your all-time favorite children’s book that you didn’t write?

Impossible question to answer. The children’s book landscape is so rich and so complex, and childhood itself is such a long, varied process. It’s very hard to compare a great picture book with a great chapter book with a great book for teenagers. And the boundaries are so fluid between children’s books and adult books, anyway. I don’t think I ever really thought of them as separate categories; I just voraciously read everything I could find that looked interesting. Many of the books that formed me, that were my favorites, were adult books which I read as a child. And in some ways, I had a very odd and old-fashioned childhood, growing up in rural Tipperary, with a lovely but old-fashioned little town library. Therefore, I didn’t read, or even come across, a lot of the more famous modern children’s books. I was slightly out of time; I was reading Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, and collections of Greek myths, and Anna Sewell’s heartbreaking Black Beauty, and Arthur Ransome’s idyllic, pre-war Swallows and Amazons series. But I was, simultaneously, also reading a lot of American science fiction; people like Fredrik Pohl, James Tiptree Jr., Philip K. Dick. And a lot of writers, like Ursula K. LeGuin, who moved effortlessly back and forth between children’s literature, like the Earthsea trilogy, and extraordinary, mind-blowing adult novels like The Lathe of Heaven. But as for specific children’s books…S. E. Hinton’s That Was Then, This Is Now really blew me away. The Tripods trilogy, by John Christopher. A Joan Aiken novel, whose name I can’t now recall, where time stops and dust hangs solid in the air...Alice in Wonderland, and Through the Looking Glass! Oh God, so many.

Is there any type of project you haven’t done, but dream of doing someday?

Writer in residence on the International Space Station would be good. I'm pretty sure I would find the view inspiring. Mars would also be terrific. Hurry up, Elon!

What’s next for you?

Well, my wife Solana is having a baby very soon indeed. So, all going well, I will be busy with a baby for a year or two. I find children absolutely fascinating; they come out with all their senses alive and alert, but for quite a while they are totally unable to make sense of what is coming in, or filter reality down to something manageable, or even to see themselves as separate from the universe. All babies are born, as the poet William Blake said, with the doors of perception thrown wide open. I love seeing the world through their eyes, and helping them navigate it. They help me see their world, and I help them see mine. We both learn a lot. That’s my next project! I’m also writing a nonfiction book about the universe as an evolved entity, but that’s a whole other story… And another Rabbit & Bear book, called A Bad King Is a Sad Thing, which I am finding impossibly difficult at the moment; but I always find them impossibly difficult, and they always turn out okay in the end.

Sign up for our mailing list to get a first look at new releases, giveaways, special events, and more!

Silver Dolphin Books

Shop by Age

Printers Row Publishing Group